From the sweltering humidity of a tropical rainforest to the biting winds of the Arctic tundra, the vast tapestry of Earth's Geography & Climate dictates not just the natural world but also the very rhythm of human civilization. Understanding this intricate dance between physical landscapes and atmospheric conditions isn't just academic; it’s crucial for navigating a rapidly changing planet. This guide unpacks the foundational principles of how our world works, the forces—both natural and human—that are reshaping it, and what we can collectively do to steer toward a more sustainable future.

At a Glance: Decoding Earth's Climates

- Weather vs. Climate: Not the same! Weather is daily, climate is long-term.

- Geography's Hand: Mountains, oceans, and latitude fundamentally shape regional climates.

- Solar Power: The sun's energy distribution is the primary driver of global weather patterns.

- Human Fingerprint: Our activities, from burning fossil fuels to deforestation, are dramatically altering climate.

- Action Required: Mitigation (reducing emissions) and adaptation (adjusting to changes) are our dual strategies.

- Global Impact, Local Burden: Climate change disproportionately affects vulnerable communities and developing nations.

The Blueprint of Our Planet: Understanding Geography's Role in Climate

Imagine trying to predict tomorrow’s picnic weather based on last year’s average temperature. Sounds silly, right? Yet, this highlights a common misunderstanding at the heart of climate science: the critical difference between weather and climate.

Weather vs. Climate: A Crucial Distinction

Weather refers to the short-term, often hourly or daily, conditions of the atmosphere. Think about what you see when you look outside: is it sunny, rainy, windy? These are elements of weather. Key components include:

- Temperature: How hot or cold it is.

- Relative Humidity: The amount of moisture in the air.

- Rainfall: Precipitation levels.

- Air Pressure: The weight of the air column above you.

- Winds: The direction and speed of air movement.

To track these elements, meteorologists use tools like thermometers for temperature, rain gauges for rainfall, barometers for air pressure, and anemometers for wind speed.

Climate, on the other hand, describes the average patterns of weather over an extended period, typically decades or even centuries. When we talk about a region having a "tropical climate," we're referring to its consistent long-term patterns of warmth and rainfall, not just a single hot day. It’s the overarching atmospheric personality of a place, influencing everything from agriculture to architecture.

Earth's Uneven Embrace: How Solar Energy Shapes Regions

The sun is the ultimate powerhouse behind most weather processes. However, Earth's spherical shape means solar energy isn't distributed equally.

- Equatorial Regions: Near the equator, sunlight hits Earth most directly. This concentrated energy input results in consistently higher temperatures and abundant rainfall, fostering lush tropical equatorial climates and tropical monsoon climates.

- Polar Regions: As you move towards the poles, sunlight strikes the Earth at an increasingly oblique angle. This scatters the energy over a larger area, leading to lower energy input and, consequently, frigid conditions year-round, characteristic of cool temperate climates or even colder polar zones.

This fundamental distribution of solar energy sets the stage for global climate zones, dictating baseline temperatures and influencing major atmospheric and oceanic circulation patterns.

Nature's Architects: Geologic Features and Their Climatic Influence

Beyond latitude and solar radiation, the physical architecture of our planet—its mountains, oceans, and prevailing winds—plays a profound role in shaping local and regional climates. These are the geologic factors that subtly, and sometimes dramatically, redirect weather systems.

Mountain Ranges & the Rain Shadow Effect

Mountains act as formidable barriers to air masses, fundamentally altering precipitation patterns. When warm, moist air approaches a mountain range from the windward side:

- It is forced to rise.

- As it ascends, the air expands and cools.

- The cooling causes water vapor to condense, forming clouds and releasing precipitation (known as orographic precipitation). This is why the windward sides of mountains are often lush and green.

- After shedding its moisture, the now drier air passes over the mountain's summit.

- As it descends on the leeward side, the air compresses and warms.

- This warmer, drier air creates a distinct dry zone known as a rain shadow, where precipitation is significantly reduced.

Examples: The majestic Himalayas cause heavy rainfall on their southern slopes while leaving the vast Tibetan Plateau to their north arid. Similarly, the Cascade Mountains in the Pacific Northwest of North America create a rain shadow that results in the dry plains of eastern Washington. The Andes Mountains in South America also exhibit this effect, contributing to the aridity of the Atacama Desert.

Ocean Currents

Oceans are massive heat sinks and distributors. Powerful ocean currents act like conveyor belts, moving warm water from the equator towards the poles and cold water back towards the equator. This global circulation system plays a critical role in moderating temperatures, particularly in coastal regions. For instance, the Gulf Stream brings warm water to Western Europe, giving it a milder climate than other regions at similar latitudes.

Prevailing Winds

Just as ocean currents move water, prevailing winds transport heat and moisture across continents. These consistent wind patterns are crucial for distributing atmospheric energy and precipitation. For example, the monsoon system, driven by seasonal shifts in wind direction, brings dramatic changes in rainfall to many parts of Asia.

A World of Climates: Zones and Their Characteristics

Combining solar energy distribution, geologic factors, and atmospheric circulation gives rise to distinct climate zones across Earth.

- Tropical Zones: Found near the equator, these regions are characterized by warm temperatures year-round and typically abundant rainfall, supporting incredibly diverse ecosystems like rainforests. These often align with tropical equatorial and tropical monsoon climate types.

- Temperate Zones: Situated between the tropics and the polar regions, temperate zones experience moderate temperatures and four distinct seasons, with varying precipitation throughout the year. Many of the world’s major population centers fall within these zones, often experiencing cool temperate climates.

- Polar Zones: Near Earth's poles, these regions endure frigid conditions, extremely short growing seasons, and limited precipitation, often existing as deserts due to the lack of moisture.

Mediterranean vs. Desert Climates: A quick comparison highlights how specific factors create unique climates. Mediterranean climates, found in places like Southern California or the Mediterranean Basin, are characterized by mild, rainy winters and hot, dry summers—often influenced by warm ocean currents. Desert climates, by contrast, receive very sparse rainfall due to high-pressure systems or prominent rain shadow effects, experiencing extreme temperatures with minimal moisture.

The Accelerating Shift: Understanding Climate Change

While Earth's climate has naturally fluctuated throughout history, we are now witnessing changes occurring at an unprecedented speed, largely driven by human activities. This rapid alteration is what we call climate change.

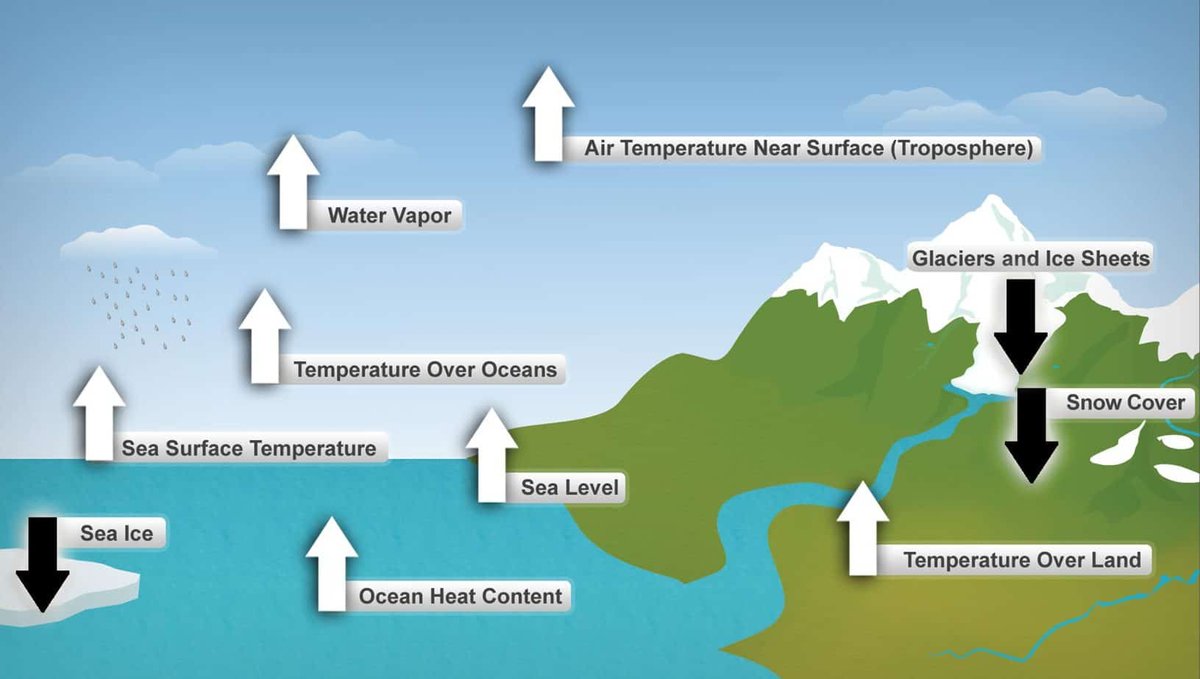

Unmistakable Signals: The Evidence of a Warming World

The scientific evidence for climate change is overwhelming and comes from multiple lines of inquiry:

- Rising Global Temperatures: Global average surface temperatures have been steadily climbing, with the warmest years on record occurring in the last two decades.

- Melting Glaciers and Ice Sheets: Glaciers worldwide are retreating, and the ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica are losing mass at an accelerated rate, contributing to sea level rise.

- Increased Frequency and Intensity of Extreme Weather Events: We are experiencing more severe heatwaves, prolonged droughts, intense rainfall, stronger storms, and altered precipitation patterns.

- Ocean Acidification: Oceans absorb a significant portion of the excess carbon dioxide, leading to changes in their chemistry.

- Sea Level Rise: Thermal expansion of warming ocean water combined with melting ice is causing global sea levels to creep upwards, threatening coastal communities.

Tracing the Threads: Natural and Human Causes

Climate change has both natural and human drivers, but the current rapid shift is primarily attributable to the latter.

Natural Drivers

Historically, Earth's climate has been influenced by:

- Earth's Orbital Variations: Subtle shifts in Earth's orbit around the sun can alter the amount and distribution of solar energy received, driving long-term cycles like ice ages.

- Changes in Solar Output: Fluctuations in the sun's energy output can have minor effects on global temperatures.

- Large-Scale Volcanic Eruptions: Powerful eruptions can release aerosols into the atmosphere, temporarily blocking sunlight and causing short-term cooling.

These natural factors typically operate over very long timescales, often tens of thousands to millions of years. They cannot explain the rapid warming observed over the last century.

Our Footprint: Human-Induced Changes

The primary driver of contemporary climate change is human activity, primarily through the release of greenhouse gases.

- Population Growth and Economic Development: A growing global population coupled with industrialization and economic development has led to an escalating demand for energy, much of which has historically been met by burning fossil fuels.

- Burning Fossil Fuels: The combustion of coal, oil, and natural gas for electricity, transport, and industry releases vast amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases (GHGs) into the atmosphere.

- Deforestation: Forests act as vital carbon sinks, absorbing CO2 from the atmosphere. Deforestation, particularly in tropical regions, not only releases stored carbon but also reduces Earth's capacity to absorb future emissions.

- Changing Land-Use Patterns: Agriculture, urbanization, and other land transformations alter local evaporation rates, temperature balances, and carbon sequestration potentials.

These activities enhance the greenhouse effect—a natural process where certain gases in the atmosphere trap some of the sun's outgoing heat, keeping Earth habitable. However, the excessive release of GHGs intensifies this process, leading to an enhanced greenhouse effect, trapping more longwave radiation and causing the planet to warm. This sets off powerful cause-effect chains: increased greenhouse gases lead to trapped longwave radiation, which results in higher global temperatures, manifesting as more frequent and intense extreme weather events.

A Cascade of Consequences: Impacts Across Systems

The warming planet triggers a complex web of environmental and socio-economic changes:

- Global Warming: The most direct consequence, leading to higher average temperatures worldwide.

- Changes in Ocean Circulations: Warming oceans and melting ice can disrupt major ocean currents, potentially altering regional climates drastically.

- Altered Precipitation Patterns: Some regions face increased droughts, while others experience more intense rainfall and flooding.

- Marine and Terrestrial Biodiversity Loss: Species struggle to adapt to rapid habitat changes, ocean acidification impacts marine life (hindering shell formation for creatures like corals and mollusks), and warming oceans affect phytoplankton, disrupting entire food webs. This leads to mass extinctions and ecosystem collapse.

- Sea Level Rise: Threatens coastal cities, displaces populations, and contaminates freshwater resources.

- Increased Extreme Weather: More frequent and severe heatwaves, wildfires, hurricanes, and floods.

- Ecosystem Disruptions: Changes in growing seasons, pest outbreaks, and shifts in species distribution impact agriculture, forestry, and natural habitats.

Unequal Burdens: Socio-Economic and Environmental Consequences

The consequences of climate change are not felt equally. Developing countries and disadvantaged communities, often with fewer resources and greater reliance on natural systems, typically face greater burdens. Their vulnerability is heightened by factors like fragile infrastructure, limited access to technology, and economic dependence on climate-sensitive sectors like agriculture. Just as geography shapes climate, socio-economic factors determine how communities cope, highlighting disparities in vulnerability, whether comparing vast continents or specific nations like Comparing Dominican Republic and Suriname facing distinct environmental challenges. Evaluating these consequences on different groups is crucial for developing equitable solutions.

Forging a Sustainable Future: Climate Action and Resilience

Responding to climate change requires urgent, stepped-up efforts. These efforts fall broadly into two categories: mitigation and adaptation.

Defining Our Response: Mitigation and Adaptation

- Mitigation Strategies: These aim to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and enhance the Earth's capacity to absorb them. The goal is to tackle the root causes of climate change.

- Adaptation Strategies: These focus on adjusting to the actual or expected impacts of climate change, learning to live with and minimize the risks from unavoidable changes already in motion.

Mastering the difference between these two approaches is fundamental to understanding climate action.

Reducing the Footprint: Mitigation Strategies in Practice

Effective mitigation involves a systemic transformation of how we produce and consume energy, manage land, and develop technology.

- Clean Energy Transition: Shifting from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources like solar, wind, and hydropower is paramount. Nations like Norway, with over 90% of its electricity coming from hydropower, demonstrate the significant potential of clean energy. Singapore, for instance, is investing S$49 million into low-carbon technologies and exploring innovative solutions like floating solar farms to maximize its renewable energy potential despite land constraints.

- Low-Carbon Technologies: Investing in and deploying technologies that reduce emissions across various sectors, from industrial processes to transportation. This includes carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS).

- Enhancing Carbon Sinks: Protecting and expanding natural carbon sinks, particularly through reforestation and afforestation. Planting trees not only absorbs CO2 but also restores ecosystems and biodiversity.

- Sustainable Urban Planning: Implementing "car-lite" policies, promoting public transport, and designing energy-efficient buildings in cities reduce emissions from transportation and energy consumption. Singapore's Green Plan 2030, for example, emphasizes sustainable living and greener infrastructure.

- Waste Management: Reducing waste generation and improving recycling rates decrease methane emissions from landfills.

Mitigation efforts aim to "bend the curve" of emissions, preventing the worst potential impacts of global warming. Their effectiveness often depends on significant initial investment, robust infrastructure, and strong political will, especially for developing nations.

Adapting to the Inevitable: Building Resilience

Even if we drastically cut emissions today, some level of climate change is already locked in due to past emissions. Adaptation strategies help communities cope with these unavoidable impacts.

- Flood Control and Coastal Protection: Building sea walls, restoring mangroves, and developing advanced drainage systems are crucial for protecting coastal areas and low-lying cities from rising sea levels and increased storm surges. Singapore's drainage adaptation measures, for example, involve extensive canal networks and pump stations to manage heavy rainfall.

- Urban Planning and Infrastructure Resilience: Designing infrastructure to withstand extreme weather events, such as heat-resistant materials for roads or elevated buildings in flood zones.

- Developing Drought-Resistant Crops: Investing in agricultural research to create crop varieties that can thrive in drier conditions or withstand higher temperatures, ensuring food security.

- Early Warning Systems: Implementing sophisticated meteorological monitoring and communication systems to provide timely warnings for extreme weather events, allowing communities to prepare and evacuate.

- Ecosystem-Based Adaptation: Using natural processes to reduce climate risks, such as restoring wetlands to absorb floodwaters or planting diverse forests to reduce wildfire risks.

Risk, Vulnerability, and Exposure: Why Impacts Vary

The actual risk a community faces from climate change is not just about the nature of the hazard (e.g., a hurricane). It's a complex interplay determined by:

- Hazard: The specific climate event (e.g., intense rainfall, heatwave, sea level rise).

- Vulnerability: The susceptibility of a community or system to the adverse effects of climate change. This includes socio-economic factors, health conditions, access to resources, and quality of infrastructure.

- Exposure: The presence of people, livelihoods, ecosystems, and infrastructure in places that could be adversely affected by climate hazards.

A highly exposed but less vulnerable community (e.g., a wealthy city with robust defenses) might fare better than a less exposed but highly vulnerable community (e.g., a remote, impoverished village with no warning systems).

Collective Action: Evaluating Strategies at Every Level

Addressing climate change demands coordinated action from individuals, communities, and governments, scaled from local initiatives to international agreements.

- International Agreements: Pacts like the Paris Agreement, signed by 195 nations, aim to align countries under a shared vision, set global targets for emissions reductions (Nationally Determined Contributions - NDCs), foster transparency, and enable financial and technological support for developing nations. While vital for collective responsibility and setting a framework, their effectiveness can be limited by voluntary compliance and geopolitical complexities.

- National Policies: Governments implement regulations, incentives (like carbon taxes or renewable energy subsidies), and infrastructure projects to drive mitigation and adaptation efforts. Singapore’s comprehensive climate strategy, encompassing national plans for energy efficiency, sustainable transport, and coastal protection, is a robust example.

- Local Initiatives: Cities and communities often lead with grassroots efforts, from promoting public transport and green spaces to developing local flood resilience plans and encouraging community gardens. These ground-level implementations, often involving low-carbon technologies and sustainable urban planning, are essential for translating broader goals into tangible changes.

Ultimately, international cooperation provides the structure for collective responsibility, but its effectiveness hinges on varying development levels, requiring financial aid, technology transfer, and capacity-building for less developed countries. It must always be paired with concrete, on-the-ground implementation and national investment.

Navigating the Complexities: Common Questions & Deeper Insights

The science of climate and geography can be intricate, but clarifying common points can build a stronger understanding.

What's the "Greenhouse Effect" versus the "Enhanced Greenhouse Effect"?

The greenhouse effect is a natural and vital process. Certain gases in Earth's atmosphere (like water vapor, CO2, methane) trap some of the heat radiated from Earth's surface, preventing it from escaping into space. This natural blanket keeps our planet warm enough to support life—without it, Earth would be a frozen wasteland.

The enhanced greenhouse effect refers to the additional warming of the planet caused by human activities that release extra greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. This excess acts like thickening the blanket, trapping more heat than natural processes would, leading to global warming.

How do we measure climate elements?

While we listed the tools for weather measurement (thermometer, rain gauge, barometer, anemometer), understanding climate involves collecting decades of this data and analyzing averages and trends. Scientists also use:

- Satellites: Monitor global temperatures, ice cover, sea levels, and atmospheric composition.

- Weather Balloons: Gather data on atmospheric conditions at various altitudes.

- Ocean Buoys: Track ocean temperatures, currents, and pH levels.

- Ice Cores and Tree Rings: Provide historical climate data, allowing scientists to reconstruct past temperatures and atmospheric compositions over millennia.

Can individual actions truly make a difference?

Yes, absolutely. While large-scale systemic changes are crucial, individual actions collectively contribute to broader shifts. From reducing your carbon footprint (e.g., choosing sustainable transport, consuming less energy) to advocating for policy changes, individual choices create ripple effects. Think of it as operating on different scales and perspectives: individuals inspire communities, which can influence governments and international bodies. Every conscious decision adds to the momentum.

What role do diagrams and data play in understanding climate?

Visual tools are invaluable for comprehending complex climate phenomena. Climate graphs illustrate long-term temperature and precipitation trends. Wind circulation maps depict global wind patterns and their influence on weather. Diagrams showing sea level rise help visualize the impact on coastlines. Understanding how to interpret these visuals—whether it's a land/sea breeze diagram or a monsoon system—is key to grasping the spatial variation and time scales of climate processes. They transform abstract data into tangible insights.

Moving Forward: Your Role in a Changing World

The story of Geography & Climate is far from over. It's an ongoing narrative where natural forces lay the groundwork, and human actions increasingly shape the plot. You've now gained a foundational understanding of the intricate physical processes behind climate patterns, the undeniable evidence of human-driven change, and the dual strategies of mitigation and adaptation that offer pathways forward.

This isn't merely about memorizing facts; it's about connecting science, society, and solutions. Think across scales—from how a mountain creates a microclimate to how international agreements attempt to manage global emissions. Incorporate geographical concepts like cause-and-effect, spatial variation, and the diverse perspectives of stakeholders. Stay updated, engage with reliable sources, and most importantly, translate knowledge into informed, sustainable actions in your daily life and within your community. Our planetary shifts are driven by both landscapes and human action, and the future climate largely depends on the actions we take today.